Gentleman's Companion,

Part II

Pauline Paulsen, a twenty-one-year-old passenger on the 1932 cruise of the Resolute, had never met anyone like Charles H. Baker, Jr., in her hometown of Spokane, Washington. Baker was downright dashing: Esquire described him as “a rugged six-foot-three, has straight features, a straight stare, and the permanent tan of a perennial sportsman.”

Their love affair was swift and intense; Franz Lehar’s love song “Dein Ist Mein Ganzes Hertz,” a favorite of the Resolute’s orchestra, became their theme. By India, they were engaged, and at that boozy cocktail party in Hong Kong, they were married (though a more traditional ceremony in the States followed a few months later). After many Rosy Dawn cocktails, the newlyweds boarded a motor launch in Victoria Harbor toting a big cloisonné tub of freesia—an improvised wedding gift from their host—and made it back to the Resolute just before sunrise.

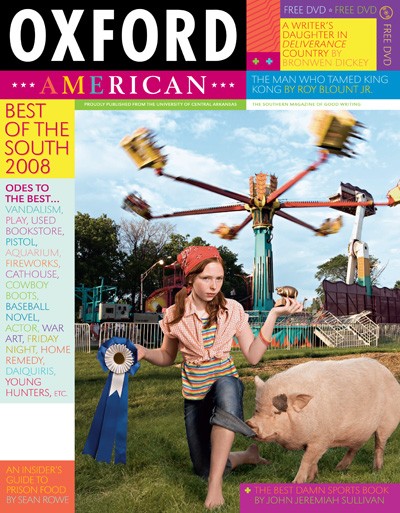

Pauline Baker née Paulsen, off the coast of Mexico, circa 1935

After meeting Paulsen, Baker wrote more than ever—though he no longer had to rely solely on writing’s skimpy paychecks for survival. In fact, neither of them would ever have to work for a living again.

Paulsen’s father, a Danish immigrant, owned shares in Hercules, a silver mine near Coeur d’Alene which became one of the most profitable in the West. After a honeymoon in England (where Pauline, in perhaps her first act of marital devotion, fetched ice for Baker’s cocktails from underneath the local fishmonger’s filets of sole), the couple traveled almost constantly, logging numerous trips to the Caribbean, Central America, and Europe. Pauline encouraged his wanderlust; she liked to recall how in the mid-1930s they couldn’t decide whether to move to Hawaii or Florida, so they flipped a coin.

By 1935, the couple had graduated from ocean liners to private yachts, sailing aboard their ketch Marmion from Massachusetts to Coconut Grove, Florida—then a true artist’s colony—and built a house called Java Head, no doubt inspired by the Indonesian leg of their fateful voyage. Their home and its extensive gardens, planted with tropical fruit trees and herbs for cooking, became a popular gathering spot for Miami’s literary society; their Christmas night party was an anticipated neighborhood event, and guests included Hervey Allen, Burl Ives, and Ernest Hemingway. Baker’s articles about hunting, fishing, and sailing appeared in men’s magazines like The Rudder and The Sportsman; in the meantime, he continued to fill his notebooks with accounts of “really interesting people,” and the recipes he collected from them in foreign ports of call.

* * *

In 1939, Baker wrote a note to Eugene V. Connett, editor of the Derrydale Press, on his yacht’s letterhead. Derrydale was known for printing exquisite and very expensive books about hunting and fishing, written by and for wealthy sportsmen; Baker convinced Connett that a two-volume set containing “exotica of food and drink” would appeal to his clientele. “I really have been around the world three times...besides sailing on my own deep water ketch. I’ve done quite a bit of hunting and fishing in odd spots. There’s no nature-faking in any of this material.” All summer Baker worked on the book at Java Head, and The Gentleman’s Companion was published that fall in an edition of 1,250, and sold for $15 (that first edition now sells for hundreds of dollars at auction). By 1942, Baker started writing columns for Gourmet and Town & Country that shared his book’s unfettered enthusiasm for the culinary cultures of the world, inviting his readers to “cruise with us on the magic carpet of your own kitchen saucepan, and share the rare flavours from many far off places.” In an age of wartime rationing and travel restrictions, Baker’s spirit of adventure was already beginning to sound nostalgic.

While he enjoyed his increasing reputation as an authority on food and travel, Baker yearned to be a novelist. His baroque writing style is the highlight of his only novel, Blood of the Lamb, published by Rinehart & Co. in 1946.

Set in the early twentieth century in the fictional town of Merrimac, Florida, the novel chronicles the misadventures of the preacher Love Gudger, a crooked, lascivious “self-elected Shepherd at a church he had picked up for debts.” Critics appreciated the novel’s gritty local color (“as though Sinclair Lewis’ Elmer Gantry had in a previous incarnation settled on Erskine Caldwell’s Tobacco Road,” one said), but criticized the plot as “loosely sketched.” The book was released at two hundred and seventy-five pages, but the manuscript was hundreds of pages longer; the editors blamed their cuts on post-war paper shortages. Baker was crushed by the book’s critical reception. Crown Publishing had just reprinted The Gentleman’s Companion, and he hoped Blood of the Lamb would establish him as a serious Southern writer. Instead, he was seen as “more of a folklorist than a novelist,” his description of Southern life sensational for all the wrong reasons. In a later paperback printing, the cover illustration features a big-bosomed washerwoman being grasped from behind by a leering yokel. The cover proclaims the work to be “a lusty novel about FLORIDA CRACKERS.” That fall, Baker left the country again.

* * *

Baker had friends who worked for Panagra and Pan-Am airlines, which were then starting to open South America to tourism from the States—his three-month sprint through most of South America’s nations was their idea. The map of the world that Baker knew had changed. Europe was ravaged; Southeast Asia, once a playground for colonialists, would have been all but unrecognizable; and the United States, still adjusting to its role as world power, had become more businesslike and buttoned-up. American companies targeted the minerals and oil reserves of South America, which attracted the kind of company that Baker never enjoyed:

the men—most of them from the States—who explore and drill and sell and ship that oil, and a somewhat wan and weary tropics-bitten regiment of mostly young and pretty, some of them sultrily amorous, wives who yearn for something different in life besides this humid petroleum-greased rat-race yet don’t know quite what it is; appear always to be trying to find out.

But it was here that Baker rediscovered his “really interesting people,” and most of them were Latin.

“When one of these hospitable Latins turns on the host act it puts our own fabled Southern brand of hospitality to shame, suh!” Baker wrote in his 1951 work, The South American Gentleman’s Companion. And if Latin men tended to be “vigorous, romantic, reckless and fatal characters,” the women were no less so. In Uruguay, Baker admired “a demitasse-sized bevy of slick sultry eager and amiable black haired young ladies…who sit about with…practically plunging waistlines”; on Chile’s beaches, Baker could not ignore the “slick and handsome magnificently hipped and breasted Chileno gals…gals who pass you indolently by with demure downcast lash and Mona Lisa smiles; swinging curvaceous small cupcakes up and down that fashionable strand with all the unreceptive innocence of a 5th grader with a big red Northern Spy for teacher.”

Aside from some trips to Europe in the 1950s (described in his final book, The Esquire Culinary Companion), this would be Baker’s last overseas adventure, and the accounts reveal the author to be a little less game for the rigors of travel. A burro sets “your Pastor down on his crupper-bone in mud” at the foot of Machu Picchu; he “panted through sambas” with a friend’s daughter, whose “drinks are just as lethal as she is darkly beautiful.” But he continues collecting recipes, and recording moments of beauty and wonder with a deft hand. Sitting on the balcony of the Club de la Unión in Guayaquíl, Baker watches the movement of the “dark pulsing Guayas River”:

Out in the stream groups of twinkling lights showed where invisible small tramp steamers lay. Two files of long narrow Indio dugouts slid silently past, upstream and down, each on its own private affairs. Small floating islands of water hyacinths starred with lovely mauve blossoms drifted by, their delicate spike blooms caught by the light from the Club windows.

Below him, a naked Native American girl pulls herself from the water, and onto a balsa wood raft.

She stood there motionless for two heartbeats, still as though cast in rain-wet bronze…. For no special reason she leaned over-side and plucked one mauve hyacinth bloom spike and thrust it into the jet mass [of her hair]. Then, only then, evidently feeling our weight of eyes on her, she looked straight up at the narrow balcony where we sat, and laughed. That young girl’s laugh was happy and fresh as the first dawn in Eden, like a pealing of small bells…. It was a nice moment, we thought: something for a man to hide away like a well-loved trinket in the safe-keeping of memory: something to be taken out and remembered at a proper time, later on.

It’s hard to imagine a more eloquent introduction to a recipe for ceviche.

* * *

Baker once attributed his robust health, even when traveling through the tropics, to the fact that “we never permitted setting sun—or at least midnight curfew—to find our mouth, throat and alimentary linings unfortified with at least a daily minimum of 1/2-a-5th of good liquor.” In his old age, Baker changed little about his routine. He wrote every day, including thousands of pages of a second novel, but threw it down his apartment’s trash chute before it was done. He drank every day, too—bourbon old-fashioneds, in an apartment overlooking the water in Naples, Florida, where he moved in 1972. His regimen didn’t hurt; he died at the age of ninety-one. “He was a bright and fascinating character,” Miami historian and longtime friend Helen Muir remembered in his obituary. “He had a touch of originality that is not around these days.”

In 1944, Baker delivered a message to wartime cooks in Gourmet.

By making cookery a game, not a chore…you approach the kitchen exactly like a modern Columbus approaching unknown shores. Preparing each new dish is like exploring new country, painting a fine canvas, or composing a new concerto. It is one of average mankind’s few chances to put forth something original, truly of himself…. And that’s where the fun comes in.

This sense of exploration, originality, and fun were part of his world—a world that disappeared even as he documented it. This is why his cookbooks, now long out of print, are treasured by the people that own them—they offer a stunning example of a life improbably well-lived. It’s not because his recipes are always successful; in fact, some are comically impractical. The Andean Snowdrift, for example, is a patently bizarre affair, more dessert than drink, made up of layers of crème de violette, crème yvette, Anis del Mono, and cream. Baker brought the recipe back from a “member of Ski Club Andino Boliviano, whose Chalet Clings like a Frozen Insect 18,000 Feet up on Awesome Mt. Chacaltaya, some 40 miles out of La Paz, Bolivia.”

At Chacaltaya’s jagged, frozen peak, a rare artifact from Baker’s past is preserved, as if mummified by the dry Andean air. The original wood-frame chalet of Club Andino Boliviano, built on a pile of stones that juts out from the mountain’s summit, still stands there, looking ready to collapse at the slightest provocation. A short, rocky, and incredibly steep ski run—the world’s highest—ends near the chalet’s door. It’s impossible to conceive of such a building being constructed today—it’s too unsafe, and utterly frivolous. It serves no practical purpose, except as a tourist destination in a city with no tourists. Today a new chalet, built safely in from the cliff’s edge, serves the very occasional thrill-seeker who makes the pilgrimage to the spectacular summit, from which the giant peaks of the Andes in three countries are visible. The building is quiet and has an air of neglect. No one here remembers how to make the Andean Snowdrift. The chalet keeps no liquor, no glasses either; the few visitors are offered instant coffee. In 1947, Baker marveled at the pluck of the club’s “amazing small membership of Bolivians, Americans, Chileans, Argentines, Europeans and expatriated Britishers,” but it’s hard to imagine them here, until one spots a framed photo on the wall. It is 1939; the men are in coats and ties, the women in stylish ski dresses. They pose on the edge of a mountain cliff, mugging with a smartly dressed snowman. They look like sportsmen, explorers, vagabonds, and writers. They look like really interesting people.