Gentlemen’s Companion

The worldly writing of the impossible-to-classify

Charles H. Baker, Jr.

by St. John Frizell

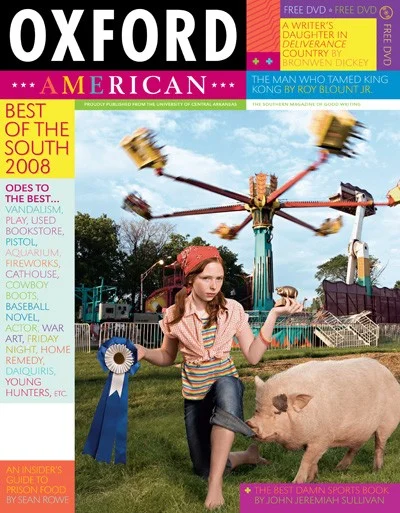

from Oxford American “Best of the South 2008,”

Summer 2008, Issue 61

Late one spring evening in 1932, the American writer Charles H. Baker, Jr., was getting mildly drunk at a cocktail party in a Hong Kong villa, high up on Victoria Peak.

The host, who was the editor of the local newspaper, had whipped up some gin cocktails; there was music and singing around a piano, and Baker kept his arm around Pauline, a beautiful heiress from Spokane. Baker and Pauline had first met several weeks earlier on board the SS Resolute, a round-the-world steamer docked that evening in Victoria Harbor.

It wasn’t Baker’s idea to get married that night, but he went along with it. A drunk colonial official turned around his coat and collar and played minister, the host gave the bride away, “and the gramophone played Mendelssohn, and there were flower girls and maids of honor, and God knows what else,” Baker wrote, years later. He loved to tell the story of how he married his third wife at a cocktail party, and he ended it, as he ended all his stories, with a recipe:

THE ROSY DAWN COCKTAIL…

For sentimental reasons this probably outranks all other cocktails in our past and present life, for it was through it’s rosy-inspired courage that we got ourselves a wife...

Take 1 liqueur glass each of the following: dry gin, orange curaçao, and cherry brandy. Add 1 tsp Rose’s lime juice, or soda fountain lime syrup. Put in a big champagne glass filled with cracked ice, stir, and fill with a touch of seltzer.

Charles H. Baker, Jr., wrote five collections of recipes that are far more than cookbooks, and impossible to classify. In the introduction to the two-volume Gentleman’s Companion (1939), Baker states his chief tenet. During his first trip around the world, he discovered that:

all really interesting people—sportsman, explorers, musicians, scientists, vagabonds and writers—were vitally interested in good things to eat and drink; cared for exotic and intriguing ways of composing them. We soon discovered further that this keen interest was not solely through gluttony, the spur of hunger or merely to sustain life, but in a spirit of high adventure.

Part travelogue, part memoir, and part instruction manual for budding bon vivants, his books and magazine columns chronicle a life spent searching for good things to eat and drink and the really interesting people with whom he loved to share them. Like his contemporaries Robert Ripley and Frank “Bring ’Em Back Alive” Buck, Baker traveled incessantly in search of unusual specimens; Baker brought his quarry home scribbled on the backs of bar napkins. In between overseas adventures, Baker fished with Hemingway off the Bimini coast; downed flaming apple brandy in the back room of a New Jersey inn with “Bill” Faulkner; joined Errol Flynn and Robert Frost for a beachfront dinner south of Miami, featuring four-inch steaks and potatoes boiled in pine resin—“better than any potato ever baked in mortal oven.” “If you ever wondered whose oyster the world is,” Esquire wrote in 1954, “meet Charles H. Baker, Jr.”

* * *

Charles H. Baker, Jr. and Ernest Hemingway, circa 1935, Bahamas

Food writers are often associated with a particular spot on a map, and for writers like A.J. Liebling, M.F.K. Fisher, and Elizabeth David, that spot was France. But Baker can’t be pinned down geographically (except with a very large map and a lot of pins). While many of the generation’s writers—Faulkner and Hemingway among them—turned a gimlet eye on the hedonism of the era’s cocktail bars and membership clubs, Baker told readers exactly what was in that gimlet—or in the Antrim Cocktail from the “Quaint Little Overseas Club in Zamboanga,” the Hotel Nacional Special from Santiago de Cuba, and the Bird of Paradise from Colón’s Strangers Club. His writing evokes Richard Halliburton, or an earlier author like Rudyard Kipling, whose lust for adventure in the world’s farthest corners was, if a little naive, at least wholly genuine and heartfelt.

Yet for a writer whose best work is based on personal experience, Baker remains unusually elusive to biographers. Like the tall tales of the best barroom raconteurs, his recollections are long on color, and short on context; he knows when to stop a story before his audience is bored, and begin the next before they can ask any questions. Details are slippery: a night that is capped by vintage Krug ’19 in one account ends with Krug ’23 in another. His anecdotes concern people who have long since vanished; they take place in hotels and restaurants that have been shuttered for decades, in countries that have changed their names. On the subject of his diet, he is effusive; on his family and early life, he is all but silent.

Among all the stories he shared, Baker rarely told the one about growing up in Zellwood, Florida, the hamlet northwest of Orlando where he was born on Christmas day, 1895. Baker adored his home state—the swamps, the islands, the water, the characters, and the climate—and, inspired by the children’s adventure books of fellow Floridian Kirk Munroe, explored as much of it as he could. When he was twelve, he pitched a tent alongside the men working on the Transatlantic Railroad, and paddled through the hidden coves of the Florida Keys in a tiny canoe, just like the heroes in Munroe’s Canoemates.

Baker rarely references his parents in his writing, and never by name. Jean Paul and Charles H. Baker were Northern industrialists transplanted from Pennsylvania, and may never have intended for their son to grow up Southern, but he did, thanks to the family’s cook, Susan Rainey, whose way with food he would remember always. She “regarded white folks’ cookbooks with about as much respect as we’d pay a book on black magic,” and cooked with an “abandon which was haughty, canny, and sly. She measured not, neither did she weigh. And she turned out some of the most succulent victuals we’ve ever set tooth in.” Instead of writing about his real family, Baker invented an extensive and thoroughly fictional family tree populated by a league of Puritanical maiden aunts—Belladonna Fittich, Deleria Fittich, Lobelia Fittich—and employs them in his writing as embodiments of outdated beliefs and customs, like temperance. In one (rare) low-proof drink recipe, Baker begins: “This is a non-alcoholic cooler of a thirst-quenching and crisp mildness that even our dear old aunt Carbona Fittich of Puritan Falls, N.H., couldn’t object to.”

In 1912, Baker met the New England Brahmins of his imagination face to face. After attending Sewanee Military Academy in Tennessee, he enrolled at Trinity College in Connecticut, and spent much of his college days insinuating himself into the high-society circles of Hartford and nearby New York City. In these “financially always indebted” years, he haunted the fringes of metropolitan nightlife. By day, he stalked the free lunch buffets at the Hotel Knickerbocker bar in Times Square. By night, he pursued other interests:

How about the time after the Art Students’ League Ball on 57th Street, across from licit Carnegie Hall, and we went with a girl who unexpectedly turned out to be painted half in gold and half in silver under her evening wrap; later ending up in our Arab Sheikh’s burnous and red turned-up shoes doing telemark turns through the snow to lace a pink satin corset on the front of General Sherman’s statue at the Plaza?

He left Trinity at the end of his junior year, married a Hartford girl (Ruth Parker, who died a year later in the Spanish flu pandemic), and went to work for an industrial abrasives manufacturer in Worcester, Massachusetts. In 1925, he came into some money “due to a happy legacy from a thoughtful grandparent of the old Pittsburgh school who believed in making steel from iron,” and the child adventurer was reborn. Asked for a “sketch of his life after leaving college” by a Trinity College questionnaire, Baker writes: “For ten years I was a mechanical engineer…then published [my] own magazine—took a trip around the world—sold my magazine—started a modern interior decorating business.” The magazine was called Zest, and his Manhattan furniture shop was called The Three New Yorkers, Inc., but his trip around the world aboard the SS Resolute—the first of three such passages—turned out to be the most profitable investment.

The Resolute was a grand, three-stack steamer, complete with a ballroom, a French chef, an orchestra, and an itinerary that included forty-five foreign ports—but was apparently too rigid for the newly-liberated engineer. In Rangoon, he jumped ship, made his way to Calcutta on a boat “carrying a mess of Mohammedan pilgrims,” and stayed in a Ballygunge bungalow with an old college friend. He saw saffron drying in the streets of Srinagar; he ate sukiyaki with a White Russian girl in Peking, in a garden “where the magnolias drifted the rose-snow of their petals against the high gray wall.” In May 1926, he lived for “several formative and happy weeks” at the Hotel Opera Daunou in Paris across the street from Harry’s New York Bar, the overseas headquarters for ex-pat Americans operated by the legendary bartender Harry McElhone.

Yet Baker devotes most of his recollections of that stay to the Tiller Girls, then the resident dance troupe at the Folies Bergere, known for their short skirts, long legs, and “breakfast ankles,” as Baker puts it, “We started at the end of the line and went along, counting off from right to left; and what dancing partners; what grand fun they were!”

At every port of call, Baker copied recipes for exotic dishes and cocktails into his notebook (more than a decade later, these notes would form the backbone of his first cookbook, The Gentleman’s Companion). When he returned to New York, Baker worked as an editor at Doubleday Doran on lifestyle magazines like Country Life and American Home. But his hunger for travel was piqued, and he became disillusioned by the crass commercialism of the publishing industry. “It was not until I launched a national magazine of my own that I learned an inside secret—an editor is both autocrat and slave,” he wrote. “While he is an autocrat over the fate of a manuscript, he is often a slave to his circulation and his advertising departments. Whoever kicks against the pricks of circulation and advertising, will go eventually into bankruptcy.”

* * *

On a rainy day in January 1931, Baker left a liquor store on Main Street in Gibraltar with several large packages and headed for the wharf, where the last tender heading back to the Resolute waited for him. The circulation and advertising departments far behind, Baker was on his second world cruise—this time, however, he was on the clock. His windfall spent, Baker supervised “world cruise publicity for what probably was currently the largest steamship house on earth,” the Hamburg-American Line; he had previously run the daily shipboard newspaper on some of the Resolute’s short Caribbean cruises. At Gibraltar, the cruise’s first port of call, he gathering recipes again, this time in a somewhat scientific manner. He had packed his steamer trunk with tools necessary to a research mixologist: jiggers, bar spoons, and “the biggest cocktail book in print…one of those thick volumes which sprouted on the damp soil of Prohibition like wan, mad mushrooms.” When the Resolute set sail, Baker set about his work, with mixed results.

By Suez, we were groggy…. By Singapore we were cellars-dry, and bought again. We literally drank our way across Siam and Cambodia…. By the time we quit Honolulu the bald-faced conclusions were plain as the nose on our face—much of the welter of mixed things with fancy names were the egotistically-titled, ill-advised conceptions of low-browed mixers who either had no access to sound spirits, or if they did have, had so annealed their taste buds with past noxious cups that they were forevermore incapable of judicious authority.

This passage, from the introduction to the second volume of The Gentleman’s Companion: Around the World with Jigger, Beaker and Glass, establishes the tone right away; the collection of recipes and advice to follow is highly selective, and always opinionated. He shows no quarter to “women’s magazines” or community cookbooks, “those cute little wire-laced jobs tossed-out into a waiting breathless world by the dear dames of the East West-Newton Covered Dish Tatting, Chowder and Marching Club.” He abhorred the gelatin fad of the 1940s, “that hysterical modern miasma of gaudy ghoulish trembly little dessert things usually based on synthetically tinted and flavored bovine hooves for their shimmy-shake.” But his indignation finds its most eloquent expression on the subject of salad. It baffled him that American diners would settle for “red-ink-cylinder oil store-bought salad dressings when you can fix a decent one in sixty seconds by the clock”—as true now as it was in Baker’s day. “Cat-sup and Chili Sauce,” he writes, belong on hamburgers; “a sincere Amateur would no more think of loading his Green Salad with either of these tomato purees than he would think of wearing his Countess Mara 4-in-hand with his dinner jacket.” He attributes these horrors to provincialism and, to a degree, xenophobia:

Creation of a proper Green Salad is a relatively simple thing, like making love or dialing someone on the telephone; still if any of the basic rules are carelessly ignored in either of these latter 2 indoor sports, all you’ll get from now to Judgment Day are black eyes and wrong numbers. To us this Salad-failure on our Continent is no minor error to be shrugged-off…. It is a culinary tragedy…. Part is undoubtedly caused by the average American’s negative reaction to anything “foreign” which seems to lack financial or aristocratic authority; and this in turn is due to the tidal-wave of foreign immigrants which broke over the States at the start of the Century…. The fact that not a single female 1st Class passenger could turn-out half as good a salad as Pancho’s or Manoel’s or Luigi’s wife coming over in the Mauretania’s steerage could whip-up blindfolded meant nothing in our lives right then, nor, apparently, now.

On that voyage, Baker hunted ducks at Oasis Lakes in Fayyoum, Egypt, and won sixty-seven rupees on a horse race at the Western India Turf Club; off the coast of Sandankan, his crippled motor launch was rescued by “a Borneo prahu, with a sail like a striped butterfly and a gent in a G-string and a headdress.” On the way back to California from Yokohama, he met a young Tahitian planter named Clymer Brooke. George Clymer Brooke had left Connecticut almost three years earlier on an expedition to collect flora and fauna; Brooke jumped ship in French Polynesia and “ended up hobnobbing with princesses on Moorea, owning some sort of vanilla plantation,” Baker recalls, in the introduction to his recipe for “Vanilla Punch.” When they met, the planter was headed back to Long Island, New York, to marry and bring his wife back to Tahiti, “like a sea-going Lochinvar.”

At age thirty-five, Baker was twelve years older than the young planter, unmarried, and rootless. He had wed again, but he never spoke about his second wife to his children; the marriage was short, and ended painfully. There were other romances. He shared a Astor Hotel Cocktail with “a Maiden by Whom We Were Later Rejected in Marriage” in Shanghai. His recipe for soupa augholemono, from the Grand Bretagne Hotel in Athens, is flavored with the memory of “young tireless, handsome, agile and elusive lady from Greenwich, whose name and genius it is not pertinent to mention.” Elusive is the key word—at the end of his second cruise aboard the Resolute, Baker was alone.